AINT-BAD Magazine was founded in Savannah, GA in 2011 and has quickly become a significant outlet for contemporary photography.

The editors feature work that helps to "make sense of culture, politics, and history" by contributing to "an ever-more urgent, critical conversation about the human condition by way of thought provoking imagery."

As the editors say, they seek to publish "fresh photography and text in support of a progressive community of artists from around the world for our printed publication, web-based forum, and periodic exhibitions and events."

The web-based forum features new material continuously, but the print version appears on a bi-annual basis.

Photographers featured on the AINT-BAD website work all over the world, but there is, happily, a definite bias toward photographers working in the magazine's home region.

Indeed, Issue 8 (Fall 2014) of the print version was entitled "The American South," about which the editors declared:

The American South is both a reality and a fiction, a

conceptual and a cultural entity. As such, it has been famously challenged and

perpetuated through photography in the form of singular iconic images in the

work of photographers like William Eggleston and in the form of the

photo-essay, bridging journalism and fine art as in the work of Walker Evans

and James Agee.

Photographers featured in the American South issue included Cody Cobb, Ashley

Jones, Tommy Kha, Joe

Leavenworth, Sophie Lvoff, Sara Macel, Caitlin

Peterson, Walker

Pickering, Jeff Rich, Whitten

Sabbatini, Clementine

Schneidermann, Brandon

Thibodeaux, Colin Todd, and Keith

Yahrling.

Also, Lexington, KY-based photographer Nicole White (See image above), Honoraray Southern Photographer Magdalena Solé, and Virginia Beach, VA-based photographer William Douglas (see image below).

Also, Wilmington, NC-based photographer Andrew Sherman (see image below).

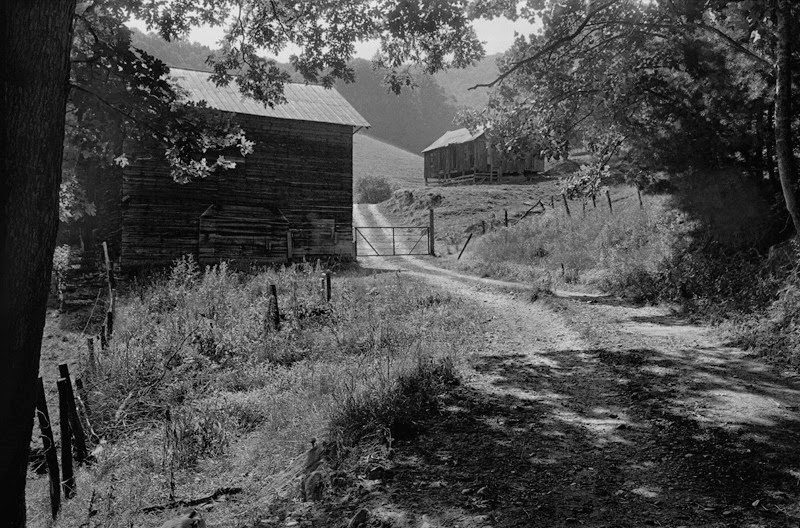

And Raleigh, NC-based (but his heart is in West Virginia) Roger May (yes the Roger May of my last two blog posts -- he's truly having a year in the sun; see image below).

And Charleston, SC-based photographer Alex Klaes (see image below).

In fact, along with photographers from across the USA and around the world, AINT-BAD Magazine features at least one photographer from the American South each month.

AINT-BAD is joining a number of other photography journals we can depend on to bring us exceptionally fine photographers from the American South.

Long may they all thrive!